Hands-On Design for AM with Chris Baschuk

3D Printing Titanium Fingers & Digital Workflows for Prosthetists

Additive Manufacturing is emerging as the preferred solution for the manufacture of prosthetic limb replacements because of the geometric flexibility, material properties and affordability of desktop FDM, and HP MJF printing in polymers.

Point Designs develops and produces articulating 3D printed titanium digits and custom polymer sockets for people with partial hand amputations. Chris Baschuk MPO, CPO, FAAOP(D), Director of Clinical Services at Point Designs shares how they got started with 3D printing, the journey of adopting a digital workflow, and how AM improves the lives of people with limb loss around the world.

Can you tell us about your role at Point Designs and what your company specializes in?

Point Designs’ goal is to restore accessibility and independence to people with limb differences by providing heavy-duty, durable and reliable, prosthetics. We specialize in manufacturing 3-D printed, ratcheting, titanium fingers for people who have partial hand or finger differences. We also offer fabrication services to prosthetists who are unfamiliar with the complex process of building a partial hand socket with fingers that are properly mounted and aligned.

We utilize additive manufacturing in the construction of the patient’s prosthetic socket and I serve in several different capacities in my role as the Director of Clinical Services. As a certified prosthetist, I am the clinical liaison with our customers and I help them decide which prosthesis is the most appropriate for their patient.

During fabrication, I’m responsible for digitizing the patient’s physical impressions, designing the final prosthesis, and preparing it for digital manufacturing. My undergraduate degree in biomedical engineering and my clinical training helps me influence Point Designs current and future products and I am a member of our R&D team.

The partial hand patient has historically been underserved and most prosthetists don’t have much experience fitting these patients with a prosthesis. My goal is to educate the prosthetist and empower them to be more independent in their clinical decision making in the future. I do this individually with clinicians and I provide hands-on training at lectures and conferences around the world.

When did Point Designs first adopt additive manufacturing and how was the engineering and business decision made to progress from prototyping components to manufacturing end use prostheses?

Point Designs was founded in 2016 and additive manufacturing was always a part of our business strategy. Our original product, the Point Digit, was designed for additive manufacturing from the ground up because traditional manufacturing methods of machining or injection molding would have made the Point Digit too expensive. Due to their low volume and high complexity, partial hand prostheses are ideal for additive manufacturing.

The original designers of the Point Digit, Dr. Richard Weir, Dr. Jacob Segil, Dr. Levin Sliker and Stephen Huddle, MS, had access to a metal 3D printer through the Veterans Administration which allowed them to design and prototype the original Point Digit. That original Point Digit was printed out of steel. With the second generation of the Point Digit, we transitioned to using titanium in the production for the reduced weight and increased strength.

Can you describe the workflow, where the interface between analog and digital processes take place and what software you use?

The process begins in a very analog form.

A prosthetist fitting their patient with our products will capture a physical, negative impression of their patient’s affected hand. This is usually done with a silicone impression material.

We’ve tried taking direct 3D scans, but because we need a high level of detail for the intimate fit of the prosthesis, we have found that silicone impressions are just a better option at this point. This physical impression is then sent to our fabrication facility where we fill it with dental stone. The dental stone model is then hand modified to prepare it for the custom HTV silicone interface. My wife, Shannon, works with me in this capacity. She is responsible for the design and fabrication of the custom HTV silicone interface that goes between the patient’s skin and the rigid portion of the prosthetic socket. Once she is done, we 3D scan the silicone interface and then I digitally design the prosthetic socket.

I use an Artec3d Space Spider and Artec Studio for my scanning and post processing. The design of the prosthetic socket occurs in nTopology and Geomagic Freeform Plus.

The first prosthesis we create is called the diagnostic prosthesis. This will have a clear silicone interface and a clear PETG printed frame. I currently print the frames in my office on a Bambu Lab X1C printer. I’ve been extremely happy with that printer. I can’t believe how fast and accurate it is with very little tinkering needed, unlike other printers like the Ender 3 S1 Pro that I’ve used in the past.

We send the diagnostic socket to the prosthetist who fits it on their patient. They will physically align the fingers and glue them in place. They send the diagnostic socket back to our fabrication team, where we digitally capture the alignment of the fingers and make any adjustments or changes to the design or shape of the socket as determined by the prosthetist during the diagnostic fitting.

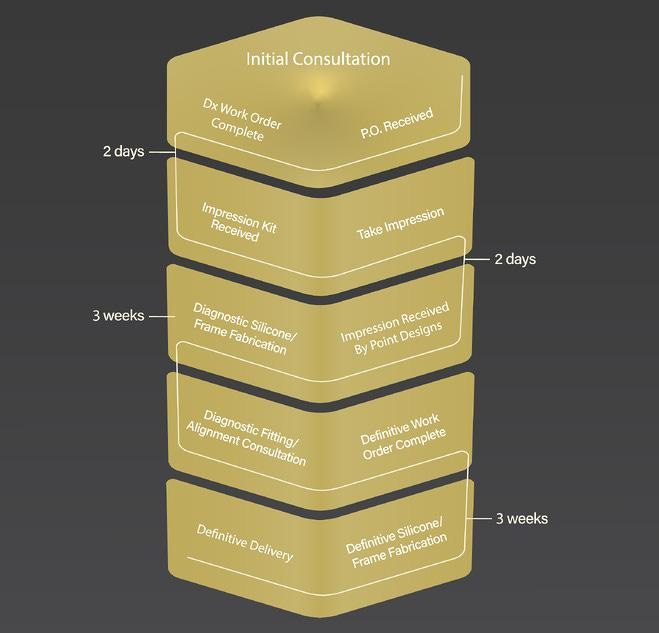

We take that information as well as the patient’s input for design choices and color into the construction of the definitive prosthesis. The definitive prosthesis is then designed, printed, assembled, and then sent back to the customer to fit on their patient. The whole process takes between 6-8 weeks from start to finish.

What manufacturing processes do you use and how were they chosen?

For the sockets, we are printing them on an HP Multi-jet Fusion printer in PA-12 nylon. Our full color prints come from a MJF580 machine and the non-color parts are printed on an MJF4200 series machine.

We currently outsource the printing to various service bureaus. Over the past several years within the prosthetics profession we have seen the MJF printing process produce very functional prostheses from a variety of manufacturers. It is a known and proven technology.

The cost of printing in PA-12 is very reasonable and the option to produce full color parts is something that our customer’s patients really like. There aren’t any other technologies out there that I’m aware of that can produce the strong full color parts that the MJF580 machines can produce.

The other reason that we elected to go with additive manufacturing for the socket construction is the repeatability of the process as well as the reduction in hands-on labor to do the fabrication. Traditional fabrication of prosthetic sockets has been done with a wet lay-up composite lamination process. This involves a lot of prep-time, chemicals, cutting, grinding, gluing, and material waste. If you mess up at any stage in the process it takes a lot of time to fix or you have to start the process over completely. It is not nearly as controlled as a process.

Ultimately what you have in mind during the design process isn’t necessarily what you end up with in the end. The traditional fabrication process really requires you to think about every step in the manufacturing process, and often you are limited by the methods available to you. Because each prosthesis is custom made, if you need special tooling for parts of your processes, you will have to design and produce those first, which takes additional time and effort.

The beauty of additive manufacturing is that the tooling that you need is digital, and it can be used over and over again, and quickly modified if necessary. Additive manufacturing allows the creating of prostheses that you couldn’t produce with traditional manufacturing methods.

Can you make a prosthesis using additive manufacturing that is the same as a traditionally fabricated prosthesis?

Sure you can, but I would push back and ask “Why would you want to do such a thing?”

The whole point is to use the principles of DfAM in the process to create prostheses that could have never been realistically produced before.

I remember a very complex prosthesis that I once made using traditional fabrication methods. The prosthesis was for someone who was missing their arm below the elbow. The prosthesis had several custom features including a BOA lacing system that was used to tighten different panels within the socket of the prosthesis as well as a custom magnetically closed door.

The whole prosthesis took me four straight 12-hour days to completely fabricate. It turned out amazing and I was quite proud of it. But it was a real pain and it was a one-off sort of project.

Fast forward a couple of years. I had someone else request the same design. They had seen the other prosthesis and they were adamant that they wanted that design.

This time around though I had the tools and resources available to digitally design it and print it. The design process took me a full day of work, but I was able to send it to the printer when it was done.

When I got it back from the printer a couple of days later, the assembly process when incredibly smooth, and honestly the fit and finish were way better than on the first traditionally fabricated prosthesis. It also weighed more than a pound less than the traditionally fabricated prosthesis.

A few months later a part on the prosthesis broke. I hadn’t made it thick enough in one spot to take the repetitive cyclical stress. However, because it had been designed digitally, I was able to make a minor adjustment to the file, print it out again, and the problem was solved. Had the failure occurred on that first traditionally fabricated prosthesis, I would have had my work cut out for me and possibly would have had to make the whole thing over.

How has the ability to 3D print titanium fingers affected the design considerations for the assembly within the mechanism?

From the outside of the fingers, they just look solid. However, the titanium printing process allows for the internal structures to be optimized for both weight and strength. They are designed in a way that would be impossible to traditionally machine in such a small, confined space. With the addition of nTopology as a design platform, we can leverage this printing technology even further through topology optimization and field driven lattice structures.

Your site shows examples of cosmetic customization of the prostheses, do you ever have requests for other more functional modifications to the base design like the Lego attachments we have seen in the past?

We get all sorts of requests from patients and clinicians all the time. Everyone is unique in what they want to be able to do with their prosthesis, and additive manufacturing usually allows us to bring their requests to life.

Recently I designed a prosthesis that had an attachment built into it for a drum stick so that a young boy who was born without any fingers could play the drums with both of his hands. That was a pretty fun project.

There seems to be an ever growing number of organizations helping to bring 3D Printed prosthetics to those who might not otherwise be able to have access or afford them including the Range of Motion Project, LifeNabled and E-Nable. Does a digital workflow from scan to print lower the level of expertise required to create a well-fitting prosthesis or are there other design factors at play that need to be considered?

The digital workflow is just an amazing new tool that allows for the creation of prostheses that we could never imagine in the past. It really is a game changer in that sense. However, they still do not replace the necessary clinical skill and decision making that a certified prosthetist has.

The socket portion of the prosthesis is the most important part of any prosthesis. If the socket hasn’t been designed and modified correctly to adapt to the anatomy of the individual wearing the prosthesis, then it doesn’t matter how amazing or “cool” the prosthesis looks, it will not be functional for the user and will just be put on a shelf or in a closet.

Prosthetists in the United States obtain a master’s degree in prosthetics and orthotics before going through a residency program and then sitting for board certification exams. The whole point of the didactic and clinical education is to teach the students how to develop functional, safe, and comfortable human body interfaces.

There are a lot of factors at play in a variety of fields including biomechanics, materials science, pathology, and psychology amongst others that have to be managed in providing a custom prosthesis to a patient. The ultimate goal is to provide functional rehabilitation to the individual through prosthetic intervention.

A digital workflow is not going to replace the clinical expertise that is required to fit a prosthesis, but it will enable the clinician to have more options to produce prostheses that better meet their patient’s expectations and goals.

I also see the digital workflow as a way that clinicians can expand their reach to those who live in areas where access to a certified prosthetist is limited.

I can think of groups like Operation Namaste, run by Jeff Erenstone, that are working to pair clinicians in Nepal with clinicians in the US and elsewhere in a mentorship program where they can share digital scans of patient’s limbs and then digitally modify them together before having the sockets printed locally in Nepal. It’s a really cool model.

Brent Wright is really blessing the lives of his patients in Guatemala through the LifeNabled foundation with his use of a digital workflow as well. He’s made some great low-cost upper limb prostheses for some of his patients down there, that just wouldn’t have been possible without the use of a digital workflow.

What do you see emerging as new trends in the adoption of AM for upper limb prostheses?

I remember in one of the Christopher Nolan Batman movies there is a scene where Bruce Wayne asks Mr. Fox to modify his batman suit to make it more flexible. The dialogue goes something like this:

Bruce: “Can you make these changes?”

Mr. Fox: “Oh, so you want to be able to turn your head?”

Bruce: “It sure would make backing down the driveway a lot easier.”

I think we are at that point in prosthetics. We need to move away from making such rigid devices and more into the space of flexible prostheses that move with the user. The PA-12 nylon material has some great material properties that can enable us to move more in that direction. The composites that we have traditionally used are just incredibly rigid.

One of the comments that we have received from our customers and their patients with regards to our 3D printed partial hand prosthetic sockets is that they really like how light weight they are, while also allowing them to have more range of motion in their remaining anatomy.

Historically the partial hand sockets were being fabricated by prosthetic technicians who are used to making lower limb prostheses. They weren’t really changing their composite lay-ups to account for the differences in forces that are experienced in a hand prosthesis as compared to a leg prosthesis. As a result, they were really overbuilt.

I think AM is going to help us build upper limb prostheses the way that an upper limb prosthesis should be built, and not be stuck building leg prostheses that are attached to arms.

I would like to thank Chris and Point Designs CEO Levin Sliker, for taking the time to share their process, images and some of the life changing work the team are doing at Point Designs.

Reach out to Chris if you are interested in learning more about 3DP prosthesis and if you are interested, Point Designs is hiring!